Know-Ask-Explore-Learn: Taking Advantage of Learner Curiosity

Chrysa Papalazarou is currently involved in the administrative side of education, but before that she has taught English to students of all ages for more than twenty years alongside writing, presenting and publishing about her endeavours to use art and foster the development of creative thinking in the ELT classroom. She is interested in how the interweaving of the aesthetic and social awareness component of artworks can introduce wider world issues to students, promote values, and contribute to a more thoughtful and creative flow in English language teaching and learning. Chrysa has created Art Least, a site on art, thinking and creativity in ELT. Chrysa is a member of the C Group and the Visual Arts Circle. She is also a member of “Worlds into Words”, an international creative writing group. E-mail: hryspap@yahoo.gr

Introduction

This article describes and reflects on a series of teaching sessions with a group of eleven-year-old 6thgraders. The sessions originated from exploiting students’ curiosity on the Chernobyl accident.

Background

We read a short text about Ukraine in our coursebooks. There was a reference in the text that aroused children’s interest and curiosity. It read:

A nuclear power plant accident in Chernobyl, in 1986, is still causing serious environmental problems which worry Ukrainian people. Today we don’t have enough drinking water supplies because of that accident.

This was a sixth-grade group (approximately A2 language level) of eleven-year-old students. They were not even born when the Chernobyl accident happened, yet these two sentences provoked a series of questions on the what, why and how of the event.

Curiosity takes the lead

Students’ curiosity and intrinsic urge to know more about the Chernobyl incident made me think it would be worthwhile to elaborate more on it. Curiosity is a major driving force in learning linked to cognitive development, education and scientific discovery. Dewey’s relevant discussion of curiosity and open-mindedness refers to the role of the teacher in keeping alive children’s “sacred spark of wonder and to fan the flame that already glows” (Dewey, 1910, p. 34).

I organised the process as a series of teaching sessions and drew on a fusion of the KWL (Know-Want to Know-Learned) strategy and the Think, Puzzle, Explore thinking routing as a supportive working framework.

KWL & Think, Puzzle, Explore

Know-Want to Know-Learned (KWL, Ogle, 1986) is mainly a reading strategy designed to assist students in navigating a text. It is constructivist in nature. It asks them to relate prior knowledge to new information, reorganise it, and get involved in constructing their own meaning and knowledge. Students first brainstorm everything they know about a topic, then they generate a list of questions about what they want to know. After reading, they record what new information they have learned. It serves to activate background knowledge, sets a purpose for reading, and helps students monitor their comprehension.

Think, Puzzle, Explore is a thinking routine (Harvard, Project Zero) that also activates prior knowledge, generates ideas, and lays the ground for further inquiry. It enables students to consider what they already know and then encourages them to identify puzzling questions or areas they wish to investigate further. Think, Puzzle, Explore comprises 3 questions:

- What do you think you know about this topic?

- What questions or puzzles do you have?

- What does the topic make you want to explore?

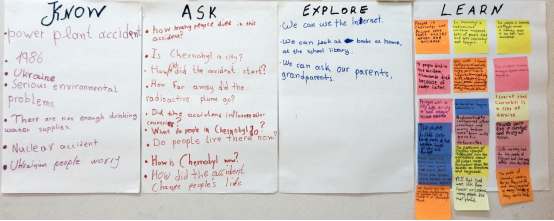

Out of these two strategies, I devised the Know-Ask-Explore-Learn version, which I found would better serve the needs of this series of sessions.

Know-Ask-Explore

This was the first part of the process focusing on the first three stems, i.e. Know-Ask-Explore.

- The first question to ask students was:

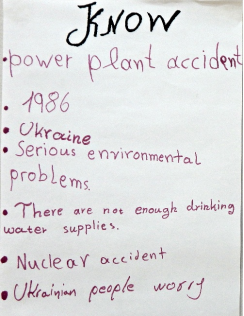

What do we already know about Chernobyl?

Here, they drew on the information they had from their coursebook excerpt. It was a brainstorming activity. Responses were shared:

|

|

Prior Knowledge:

|

Figure A: student responses in the brainstorming stage

- The second question was:

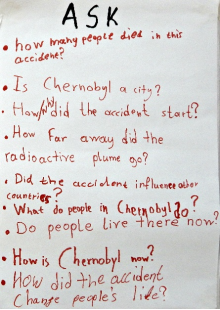

What questions do you want to ask about the Chernobyl accident?

|

|

The questions that emerged:

|

Figure B: student questions

- The next question was:

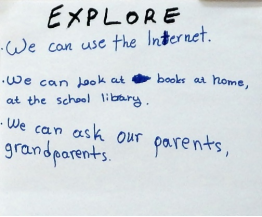

How do you think we can explore these questions?

The ‘Explore’ stem, drawn from the Think, Puzzle, Explore thinking routine described above, would lay the ground for independent inquiry.

|

|

‘Explore’ suggestions:

|

Figure C: student ideas for ways of exploring the topic

After the ‘Explore’ stem, students chose which question they wanted to work on and their preferred mode of work (individually, in pairs). The general guideline for those who would be searching on the internet was not to be lost in a plethora of information. It is often the case when students are assigned schoolwork of this kind that they come up with long, incomprehensible texts copied and printed from internet resources over which they have little control or understanding. I asked if they would rather come up with small texts (3-6 lines) focusing on the question they had chosen. They would also have to be able to present their responses in class, explain new vocabulary to their classmates, and be prepared to answer their questions.

Reporting back

Students worked on the question/s of their choice at home. In the next session, during the reporting stage, they presented the outcome of their independent inquiry, answered their classmates’ questions and took notes of the other responses shared in class. Class discussion yielded a wealth of information and expanded knowledge on the incident covering all the ‘Ask’ components of the previous session.

|

|

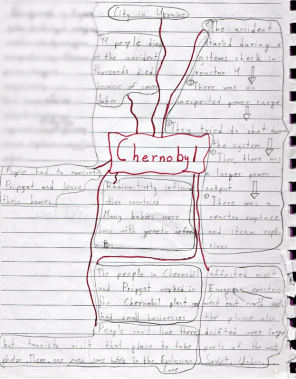

Knowledge gained through the inquiry stage:

|

Figure D: student notes of the class discussion

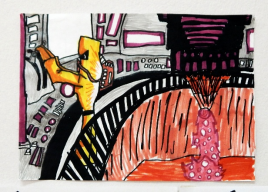

Creative non-verbal responses were also noted.

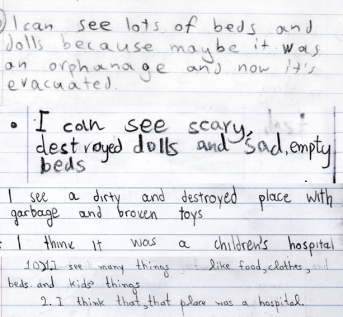

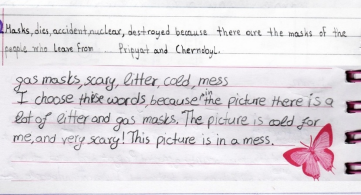

Figure E: student drawings of the Chernobyl accident

The teacher steps in

The next step was two-fold

First, students were given a worksheet to cater for some extra practice and consolidation of the language that had emerged in the previous session.

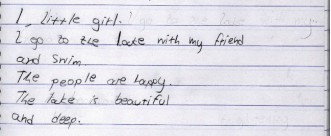

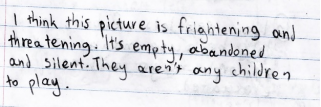

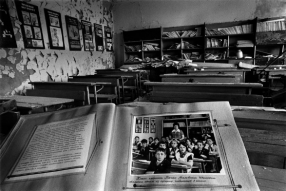

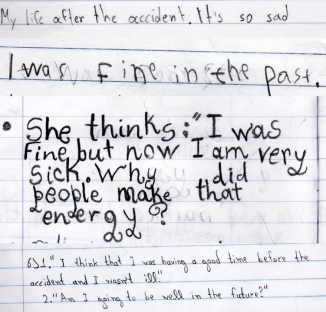

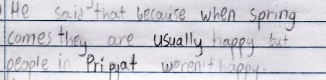

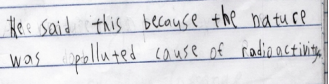

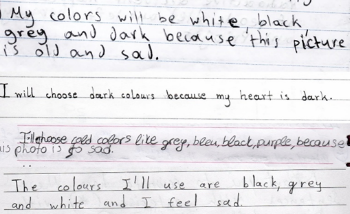

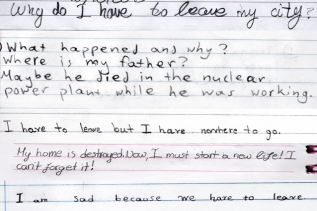

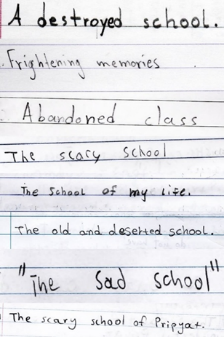

Then, a series of images (nine in total) was used to encourage more emotional, empathetic and creative understanding of the Chernobyl accident. After showing each image there was a question students had to respond to, individually or in pairs. A time limit of a few minutes was set. The visuals invited students to reflect on different aspects of the Chernobyl accident and its impact on the lives of the inhabitants.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure F: sample student responses to the visual prompts

Learn

The final step involved reflecting by providing answers to the ‘Learn’ component:

- The question was:

“What new things have we learned about the Chernobyl accident?

|

|

Figure G: student responses to the ‘Learn’ component

Figure H: class chart documentation of the Know-Ask-Explore-Learn strategy

The fabric of this learning experience

This learning experience combined language, visual literacy, and environmental awareness. Learning points included the following:

In terms of language:

- encouraging reading with the aim to focus on key elements relevant to the topic

- practising question asking

- eliciting and introducing vocabulary relevant to the topic

- encouraging speaking and active listening i.e. listening that utilises their classmates’ ideas and opinions

- practising note-taking and realising its importance as supportive material in writing activities

- having students consolidate and practise new language through a series of activities

- fostering students’writing skills as a response to visual prompts and catering for a variety of products like writing poems, providing titles, expressing feelings and impressions, imaginings etc.

- fostering a cross-thematic approach by linking English with Geography and Environmental Studies

In terms of visual literacy:

- encouraging visual literacy micro-skills of careful viewing, observing, describing and analysing (photograph details)

- encouraging students’ visual literacy micro-skills of visual thinking by allowing meaning-making through both modes i.e. photographs and language

In terms of art and creativity:

- encouraging students’ creative expression

In terms of environmental awareness:

- raising awareness of the dangers of nuclear energy

- developing students’ critical thinking so as to approach relevant issues with an inquiring mind

In terms of pedagogy:

- encouraging independent student inquiry

- collaboratively building knowledge on the topic

In conclusion

A loose working framework for a learning instance that could take advantage of learner curiosity would be:

- identify a point of interest/curiosity, be alert

- apply the KAEL strategy starting from the first 3 stems (KAE)

- sized sheets f paper, KAEL worksheets can all work as means of documentation. You can also simply ask students to jot down in the notebooks their answers to the first 3 stems

- hold a plenary discussion after the ‘Explore’ stem

- encurage active listening and note-taking during the sharing of ideas, model correct language, be an example of note-taking yourself by using the board or the interactive board. This will cater for differentiation and aid less able learners

- help students consolidate and practise the new language

- either prepare wrksheets based on the language that has emerged during the classroom or ask students to write short paragraphs/texts describing classroom experience and reflecting on the lesson

- provide intriguing visual input and dress it with activities that encourage them to use the language creatively and explore the topic in question

- finish with the ‘Learn’stem

- make sure yu record all ideas shared by students. The classroom board (or interactive board), post-it notes, sheets of paper on the classroom wall, digital apps like padlet can help to this end

References

Dewey, J. (1910) How we Think. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/37423/pg37423-images.html

Maley, A., Duff, A., and Grellet, F. (1980) The Mind’s Eye: Using pictures creatively in language learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Ogle, D. (1986) “K-W-L: A Teaching Model that Develops Active Reading of Expository Text”, The Reading Teacher, Vol. 39, No. 6. International Literacy Association and Wiley: 564-570.

Visible Thinking, Think Puzzle Explore routine

Acknowledgements/Resources

Questions for images 1, 4 and 9 were found and adapted from The Mind’s Eye: Using images creatively in language learning (Alan Maley, Alan Duff and Françoise Grellet).

Images 1, 5 and 7 were found in the post Photos of Everyday Life in Pripyat before the Chernobyl Disaster.

Image 2 (Bumper cars riddled with rust) was found in the article The Ghost city of Chernobyl: Eerie pictures that show abandoned disaster zone as world marks 25 years since worst nuclear meltdown in hisory.

Images 3, 4 and 6 are from Pierpaolo Mittica’s project “Chernobyl: The Hidden Legacy”.

Image 8 (Pripyat Kindergarten) by Gerd Lundwig

Image 9 (Pripyat Middle School, gas masks on a classroom floor) by Darren Ketchum.

Danny Cook’s video “Postcards from Pripyat, Chernobyl”

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

Know-Ask-Explore-Learn: Taking Advantage of Learner Curiosity

Chrysa Papalazarou, GreeceThe Teacher, the Poet and the Critic: Change Cannot be Postponable

Fernanda Felix Binati, ColombiaTelling Their Stories to the World – Showing Support and Expressing Admiration for the Children of Gaza

Haneen Khaled Jadallah Palestine and UK;David Heathfield, UKMore than Methods: Using Stories to Humanize CPD: An Interview with Alan Maley

Chang Liu, China and UK