- Home

- Various Articles - Motivation and Engagement

- A survey on Learning Motivation of Senior English Majors Between Some Public and Private Universities in Ho Chi Minh City

A survey on Learning Motivation of Senior English Majors Between Some Public and Private Universities in Ho Chi Minh City

Tran Bao Huan, an undergraduate student at Van Lang University and a candidate for Master degree, has great interest in learning motivation and its teaching implication. He aims to hone his skills with a master degree in the upcoming years. Email: phuan126203@gmail.com

Abstract

This research investigates the similarities and differences in English learning motivation among senior English majors from some public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City. The study hired a quantitative technique with a questionnaire survey carried out amongst 180 students, similarly, divided among the two companies. The findings discovered that each intrinsic and extrinsic factors played good sized roles in motivating students, with professional desires and personal hobby rising as dominant drivers. Private college students demonstrated stronger intrinsic motivation, more structured learning behaviors, and faced psychological barriers such as low confidence and peer pressure. In contrast, public university students exhibited more uniform motivation tied to institutional requirements and relied more on peer support while struggling with infrastructural challenges. Based on the findings, recommendations were proposed to enhance English learning environments, diversify teaching methods, and support students’ psychological well-being. The study also acknowledged several limitations, including its restricted participant scope and the use of self-reported data.

Introduction

In Vietnam, English proficiency has become a crucial skill for global integration. This is driven by economic growth and international collaboration. As the country’s economy has expanded, the demand for English skills has surged, making it a critical requirement for accessing competitive job markets and higher education opportunities. Research indicates that university students in Vietnam see English not just as an academic requirement but as a gateway to professional development and cultural engagement. However, the growing importance of English also creates challenges, such as increased academic pressure and unequal access to resources, especially across different socioeconomic groups. Motivation is a key factor that affects the success of second language acquisition (SLA). Early research by Gardner (1985) introduced two central forms of motivation: integrative and instrumental. Integrative motivation reflects the learner's choice to connect with the lifestyle and people of the goal language, at the same time as instrumental motivation focuses on the practical benefits, which includes profession development or academic achievement. These concepts remain foundational in SLA research, as they shape how learner technique language getting to know (Gardner, 1985).

Despite these developments, research on language learning motivation in Vietnam is still limited, particularly regarding the differences between public and private universities. Existing studies have mostly focused on broader trends or specific student groups, without exploring how motivations might differ across institutional types. For example, the Bangkok study found distinct motivational patterns between public and private school students, influenced by differences in available resources and institutional priorities (Inngam & Eamoraphan, 2014). Similar disparities may exist in Vietnam’s higher education system, where public universities often rely on traditional teaching methods and limited resources, in contrast to the more modern facilities and diverse curricula typically offered by private universities.

This study aims to fill these gaps by focusing on senior English majors in Ho Chi Minh City, which serves as a small area of Vietnam’s educational and economic environment. Understanding these differences is important in developing effective strategies to enhance the student learning experience. Moreover, exploring the challenges that students from diverse backgrounds face can help refine language education policies. Research suggests that tailoring teaching strategies to align with students' motivational drivers can significantly improve their engagement and learning outcomes. By examining the motivational dynamics across public and private university contexts, this study seeks to provide valuable insights for educators and policymakers, contributing to a more effective and equitable approach to second language education in Vietnam.

The primary objectives of this study are to compare the learning motivation of senior English majors from some public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City, aiming to identify key similarities and differences in motivation factors. The study will explore a range of factors, both objective and subjective, that influence students' motivation to study English, without focusing solely on specific elements such as family financial background, university entry scores, or institutional reputation. The research will also examine the general characteristics of students from public and private universities and how these characteristics may impact their motivation. Additionally, the study seeks to provide practical insights and suggestions for enhancing learning motivation among English majors with diverse backgrounds. By accomplishing these objectives, the study aims to contribute to the existing literature on motivation in language learning within the Vietnamese educational context. To achieve the objectives of the study, the following research questions will be explored:

Research question 1: What are the key internal and external factors that affect students’ English learning motivation?

Research question 2: What are the similarities and differences in the factors influencing the learning motivation of senior English majors in public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City?

Literature review

Theory of motivation

Motivation has been recognized as a vital element in influencing behavior and learning. Various psychological theories have attempted to explain motivation from distinct perspectives, providing a comprehensive understanding of its nature and impact.

1 Behavioral views

Behavioral theories awareness on extrinsic motivation, in which actions are pushed by means of external rewards or punishments. Skinner’s operant conditioning idea emphasizes reinforcement, suggesting that behaviors may be bolstered via rewards. For example, a pupil may also perform properly academically to receive reward or accurate grades. However, reliance on extrinsic motivators has barriers, as it can lessen intrinsic motivation and fail to preserve lengthy-time period engagement in mastering (Cameron & Pierce, 1994; Ryan & Deci, 1996, as stated in Shirkey, 2003).

2 Cognitive views

In contrast, cognitive theories emphasize internal processes, proposing that motivation stems from the need to achieve equilibrium in one’s understanding of the world. Based on Piaget’s theories, cognitive approaches highlight the role of schema modification in responding to new experiences and resolving cognitive dissonance. These theories suggest that students are motivated to learn to achieve a sense of mastery and consistency in their perceptions (Festinger, 1957). However, cognitive views also face challenges in measuring internal motivational factors and achieving optimal disequilibrium for learning.

3 Humanistic views

Humanistic theories, consisting of Maslow’s hierarchy of wishes, attention on intrinsic motivation pushed by means of private growth and achievement. Maslow’s version outlines five levels of desires, starting with physiological and protection desires, accompanied by belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization. This framework emphasizes the significance of addressing simple desires before better-degree achievements can be pursued. Despite its influence, practical application of this theory is often limited by resource constraints (Maslow, 1970).

Types of Motivation

1 Integrative and Instrumental Motivation (Gardner’s Theory)

In second language acquisition, the principles of integrative and instrumental motivation have lengthy been essential in explaining why individuals pick to study a foreign language. According to Gardner and Lambert (1972, as referred to in Anjomshoa & Sadighi, 2015), integrative motivation refers back to the learner's desire to combine into the culture of the language network, fostering an emotional connection to the speakers and their values. This kind of motivation is going beyond absolutely gaining knowledge of the language; it's miles approximately turning into a part of the network, sharing in its subculture, and growing relationships with its contributors. For integratively motivated beginners, the language serves as a bridge to hook up with others, understand their ways of life, and have interaction in meaningful interactions. This intrinsic force to be commonplace by means of a network can beautify language studying, as it tends to be extra for my part rewarding and enjoyable.

On the other hand, instrumental motivation is often characterized by practical goals, where learners pursue a second language to achieve specific objectives such as improving career prospects, meeting academic requirements, or reading professional literature (Gardner & Lambert, 1972, as cited in Anjomshoa & Sadighi, 2015). For instance, learners who are instrumentally motivated may focus on language acquisition to gain access to better job opportunities, secure promotions, or pass examinations. This motivation is typically more extrinsically driven, as the learner's primary focus is the tangible outcomes that the language can provide, such as career advancement or higher education credentials.

Both types of motivation have been found to significantly influence language learning success, but their effects may differ based on individual contexts. Some researchers argue that integrative motivation leads to more successful language learning. Because it fosters a deeper and more lasting commitment to language learning. This is especially true when learner motivation involves a genuine interest in the culture and language speakers (Anjomshoa & Sadighi, 2015). On the other hand, instrumental motivation can lead to effective language learning. However, as Anjomshoa and Sadighi (2015) point out, these two forms of motivation are not mutually exclusive. And learners can experience a combination of both motivations. For example, learners have practical reasons for learning a language, such as for professional purposes. But one can also develop a unified desire to understand and appreciate the culture associated with that language.

Additionally, motivation in language learning is dynamic and can evolve over time. It is encouraged by using diverse inner and external factors, and the character of motivation can also exchange depending on the learner's reports, desires, and social context. Anjomshoa and Sadighi (2015) emphasize that information about these motivations is crucial for designing powerful foreign language coaching techniques, as educators can tailor their tactics to deal with each instrumental and integrative motivations, supporting newbies to acquire their favored consequences.

2 Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are two essential standards in information human behavior and the motives behind individuals' actions. Intrinsic motivation refers to undertaking an interest for the inherent delight and leisure derived from the challenge itself, as opposed to external rewards. Deci and Ryan (1985) highlighted that intrinsic motivation stems from the organismic wishes for competence and self-dedication. For instance, people are intrinsically motivated when they engage in activities such as painting or gardening, driven by their passion and the joy of the activity itself (Bontempi, 2023). White (1959) further described this type of motivation as "reflectance motivation," emphasizing the innate desire to interact competently with the environment as a reward in itself.

On the other hand, extrinsic motivation entails performing a venture to attain external rewards or keep away from punishment. These rewards can variety from tangible incentives such as cash and accolades to intangible reinforcements like reward and recognition (Bontempi, 2023). Vincent and Kumar (2018) categorize extrinsic rewards into finishing touch-contingent rewards (earned via completing a project), performance-contingent rewards (primarily based on overall performance), and sudden rewards. Unlike intrinsic motivation, that is increase-orientated, extrinsic motivation regularly aligns with achieving precise dreams, consisting of incomes, a diploma or advancing one’s career.

While intrinsic motivation encourages exploration and personal growth, extrinsic motivation is frequently linked to external validation and achieving concrete outcomes. Understanding the interplay between these motivational types is crucial for creating strategies in education and work environments to foster both personal fulfillment and goal attainment.

3 Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985)

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), brought with the aid of Deci and Ryan (1985), is an organismic theory of human motivation that emphasizes the significance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness as fundamental psychological needs. These needs are critical for fostering private boom, psychological integrity, and typical properly-being. The principle contrasts sharply with in advance mechanistic tactics, inclusive of psychoanalytic and behavioral theories, which regarded human behavior as typically driven by unconscious impulses or outside stimuli-reaction associations. Instead, SDT acknowledges the importance of volition, autonomy, and the capacity for self-route in human behavior, acknowledging the function of intrinsic motivation as a significant idea in mental development.

A one of a kind element of SDT is its differentiation among behaviors with an internal perceived locus of causality—wherein movements stem from authentic private pursuits and values—and people with an external perceived locus of causality, stimulated by external demands or pressures. This distinction permits for a nuanced exploration of self-determined versus non-self-decided behaviors.

The theory comprises three interconnected mini-theories. Cognitive Evaluation Theory makes a speciality of how external factors, including rewards or comments, can either decorate or undermine intrinsic motivation depending on their impact on autonomy and competence. Organismic Integration Theory explores the technique of internalizing outside rules, remodeling them into personal values that align with one's self-idea. Finally, Causality Orientations Theory examines individual differences in motivational orientations, identifying autonomous, controlled, and impersonal styles that influence how individuals regulate their behavior and interact with their environment.

SDT's comprehensive framework has been widely applied in diverse contexts, including education, psychotherapy, workplace environments, and sports. For example, it has been used to design educational practices that promote intrinsic motivation by fostering autonomy-supportive learning environments. Similarly, in the workplace, SDT informs strategies to enhance employee engagement by aligning tasks with individual values and providing opportunities for meaningful contributions. By addressing the complex interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, SDT offers valuable insights into the conditions that support optimal human functioning and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Challenges in language learning motivation

Language learning motivation is a dynamic and multifaceted construct. But several challenges continue to impede its effective development and maintenance. Based on insights from many research studies. These challenges can be divided into individual, contextual and systemic factors:

1 Lack of specificity in motivation research

Research on second language acquisition (SLA) motivation has often failed to address the specific processes involved in language learning. Focusing instead on broad motivational constructs (Dörnyei, 2020), this lack of specificity limits the applicability of motivational theory to real language learning contexts.

2 Sustainability of motivation

Maintaining motivation over time is a persistent challenge. Learners often lose enthusiasm due to unrealistic expectations, slow progress, or external pressures (Yılmaz & Sahan, 2023). Moreover, as Teravainen-Goff (2022) points out, even motivated learners might disengage due to factors such as fear of failure, lack of self-confidence, or insufficient support from instructors and peers.

3 Contextual and environmental barriers

The learning environment plays a critical role in motivation. Limited opportunities to practice the language, especially in real-life contexts, reduce the effectiveness of motivational efforts (Teravainen-Goff, 2022). Furthermore, institutional constraints, inclusive of rigid curricula or inadequate teacher training, exacerbate these issues (Yılmaz & Sahan, 2023).

- Psychological and emotional factors

Language learners frequently face anxiety, fear of judgment, and occasional self-efficacy, which negatively impact their motivation to have interaction in communicative practices (Dörnyei, 2020; Teravainen-Goff, 2022). For example, inexperienced learners might also avoid speaking activities to steer clear of criticism or embarrassment, similarly hindering their development.

- External and systemic challenges

Economic, social, and cultural factors also present significant barriers. For instance, learners from disadvantaged backgrounds may lack access to quality learning materials or supportive environments, leading to demotivation (Yılmaz & Sahan, 2023). Additionally, global economic shifts and job market demands often create pressure for learners to achieve unrealistic language proficiency goals quickly (Teravainen-Goff, 2022).

Similarities in learning motivation between public and private universities

Students from both public and private universities share notable similarities in learning motivation, as demonstrated in various international studies. These shared motivations often stem from intrinsic factors such as the desire for self-improvement and mastery of knowledge, as well as extrinsic factors including career aspirations and societal expectations.

Mazumder and Ahmed (2014) performed a comparative examination among university students in Bangladesh and observed that each public and private university students are pushed by using the want to secure better professional possibilities. Extrinsic motivation, including the choice to satisfy own family expectancies and societal norms, plays a good-sized role in shaping students’ educational dreams throughout both sectors. Furthermore, intrinsic motivation, which includes private hobbies within the difficulty to be counted and intellectual curiosity, is equally accepted in each corporation.

Similarly, Mazumder (2014) examined student motivation in different cultural contexts, including Bangladesh, China, and the United States, and identified a shared emphasis on goal setting and persistence among students from public and private universities. The study revealed that students across institutional types strive to overcome academic challenges, with motivation fueled by the long-term benefits of higher education, such as economic stability and personal growth.

In addition, Yılmaz and Sahan (2023) highlighted that both public and private university students value the role of academic success in achieving their future ambitions. Their study of higher education learners identified that students from both types of institutions are motivated by a combination of personal aspirations, such as self-fulfillment, and external factors like competitive job markets.

These findings suggest that despite differences in institutional settings, students from public and private universities exhibit similar motivational patterns. Both groups are driven by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, emphasizing the universal nature of learning motivation across higher education contexts.

Differences in learning motivation between public and private universities

Research indicates distinct differences in the learning motivation of students attending public and private universities, primarily shaped by variations in institutional structure, cultural expectations, and resource availability. These differences influence how students perceive their educational experiences and pursue academic success.

One prominent difference lies in the nature of extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation. Students at private universities often exhibit higher extrinsic motivation, driven by career-focused goals and financial investments in education (Mazumder & Ahmed, 2014). Private university students may feel a stronger obligation to excel academically, as their education is typically associated with higher tuition costs and the expectation of obtaining well-paying jobs after graduation (Mazumder, 2014). In contrast, public university students tend to demonstrate greater intrinsic motivation, stemming from a broader sense of intellectual curiosity and a focus on academic achievement rather than immediate financial outcomes (Mazumder et al., 2014).

The availability of resources also contributes to these motivational differences. Private universities often provide smaller class sizes, more individualized attention, and access to advanced facilities, which can enhance students' engagement and motivation (Mazumder & Ahmed, 2014). Public university students, on the other hand, may rely more on personal resilience and self-discipline due to larger class sizes and fewer individualized learning opportunities (Mazumder, 2014).

Cultural and societal expectations further shape these differences. Private university students frequently encounter pressure from family and societal norms to excel academically due to the prestige associated with attending private institutions (Luo et al., 2017). Public university students, while also motivated by societal expectations, may prioritize communal values and personal development, fostering a different type of academic drive (Mazumder & Ahmed, 2014).

Lastly, differences in long-term satisfaction and educational goals reflect varying motivational patterns. Private university graduates often express satisfaction linked to their ability to secure lucrative careers, while public university graduates emphasize intellectual fulfillment and contributions to societal development (Luo et al., 2017).

These findings highlight how institutional and cultural factors shape learning motivation, offering valuable insights for educators aiming to address the unique needs of students in both public and private universities.

Research method

This study employs a quantitative research design to investigate the factors influencing English learning motivation among senior English majors. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data from participants at six selected universities in Ho Chi Minh City. The collected responses were statistically analyzed to explore patterns, differences, and relationships among motivational factors between students from public and private institutions. The primary data collection tool was a structured questionnaire administered via Google Forms. The questionnaire was developed based on motivational theories discussed in Chapter II, particularly Gardner’s (1985) socio-educational model and Dörnyei’s (1994) motivational framework. It comprised 12 closed-ended items covering topics such as students’ prior English proficiency, reasons for learning English, study habits, motivational influences, and challenges encountered during the learning process. To ensure internal consistency and reliability, a pilot study was conducted prior to the main data collection. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated using Python and yielded a score of 0.7933, indicating good reliability.

This study was conducted among senior English majors born in 2003, currently enrolled at selected public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City. The research focused on six institutions, including three public universities—Saigon University, Ho Chi Minh City University of Education, and Ho Chi Minh City University of Foreign Languages and Information Technology (HUFLIT)—and three private universities—Van Lang University, Hoa Sen University, and HUTECH University. These institutions were selected for accessibility, program relevance, and a balanced representation of public and private sectors. Entrance scores in 2021 ranged moderately (24–27 for public; 16–19 for private), ensuring comparable academic levels and minimizing bias. This selection also reflected different educational environments, with public universities emphasizing academic rigor and private ones focusing more on practical skills and internationalization. A total of 180 valid responses were collected, with an equal distribution of 90 respondents from public universities and 90 respondents from private universities. This balanced sample was selected to allow comparative analysis between the two groups regarding their English learning motivation, learning behaviors, perceived challenges, and institutional support. Initially, over 200 responses were collected, but only 180 valid samples were selected after screening based on the study’s criteria.

Findings and discussion

Motivational factors for learning English

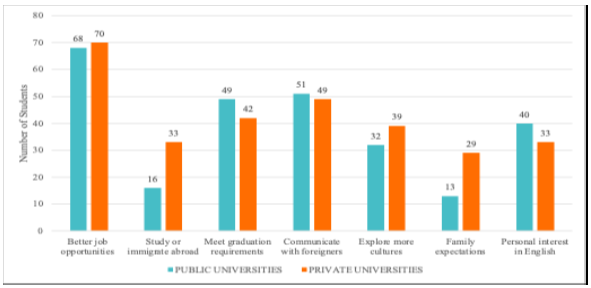

The data revealed that both public and private university students are primarily motivated to learn English for career advancement, communication, and graduation requirements. Specifically, “To have better job opportunities” was the most common reason in both groups, followed by “To communicate with foreigners” and “To meet graduation requirements.” While public university students prioritized graduation requirements and communication needs more, private university students showed stronger interest in personal development and opportunities to study or work abroad.

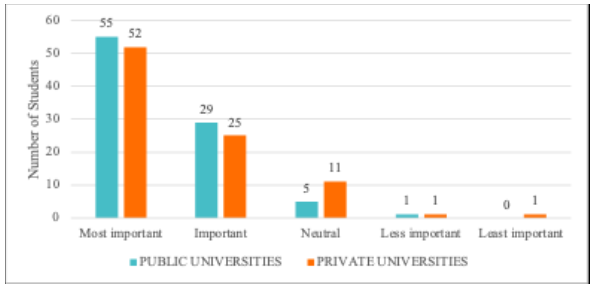

Figure 4.1: Reasons for Learning English: Public vs. Private Universities

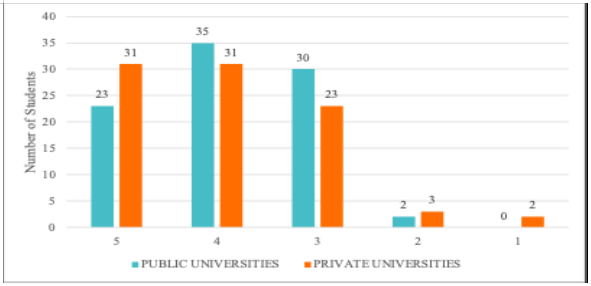

In terms of motivation levels, the majority of students from both groups reported high motivation, especially at levels 4 and 5 on a 5-point scale. However, private university students showed greater variation, including both very high and very low motivation levels, whereas public university students’ responses were more concentrated at moderate to high levels.

Figure 4.2: Self-Reported Motivation Levels for Learning English: Public vs. Private Universities

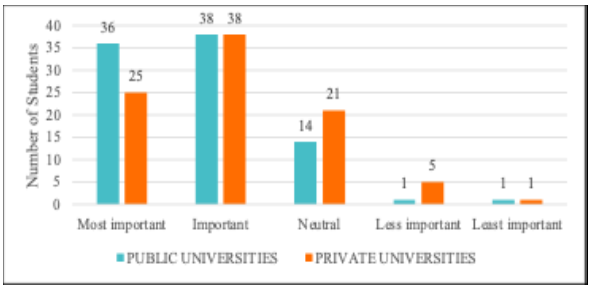

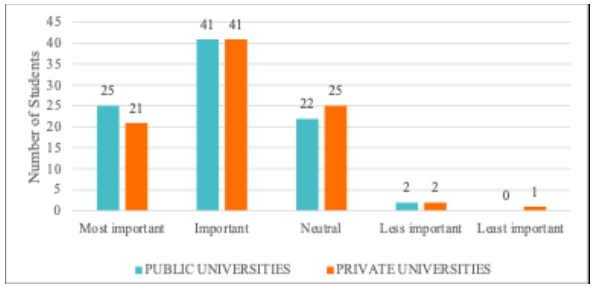

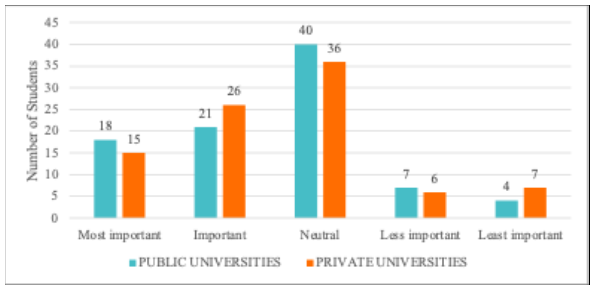

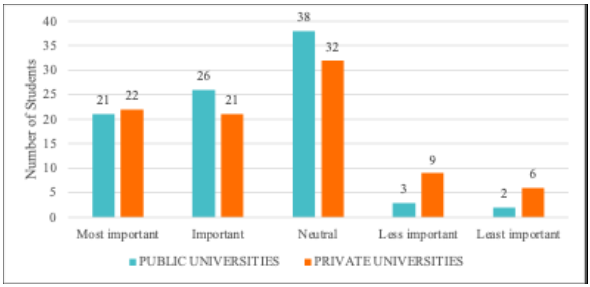

When analyzing specific motivational factors, both groups rated “Personal Interest in English” and “Future Career Opportunities” as the most important. Conversely, “University Requirements” and “Social Pressure: Family and Peer Expectations” were perceived as less influential, particularly among private university students, who showed more diverse opinions and a higher proportion assigning lower importance to these external motivators.

Figure 4.3: Importance of Personal Interest in English: Public vs. Private Universities

Figure 4.4: Importance of University Requirements: Public vs. Private Universities

Figure 4.5: Importance of Future Career Opportunities: Public vs. Private Universities

Figure 4.6: Importance of Social Pressure: Family and Peer Expectations: Public vs. Private Universities

Regarding “Scholarships or Study Abroad Opportunities,” this factor was considered moderately important by both groups, yet private university students showed a slightly higher rate of deeming it as less important. This may reflect different financial backgrounds or perceived accessibility of such opportunities.

Figure 4.7: Importance of Scholarships or Study Abroad Opportunities: Public vs. Private Universities

Open-ended reactions strengthened these findings, many students emphasized career goals, alumni achievements and aspirations to work as strong motivations in international environment. Some also cited institutional demands and colleague competition as additional factors, although they appeared less prominent.

Overall, personal interest and future career goals such as internal inspiration emerged as primary drivers of English learning, private university students demonstrated a wide range of motivational effects compared to their public counterparts.

Learning behaviors

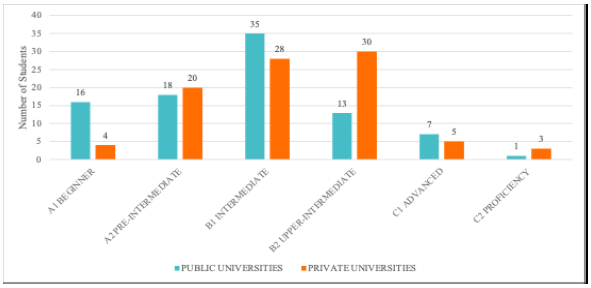

The analysis of students’ self-reported English proficiency upon entering university revealed notable differences between the two groups. Public university students reported predominantly intermediate levels, with B1 (Intermediate) being the most common, followed by B2 (Upper-Intermediate) and A2 (Elementary). In contrast, private university students had a higher proportion at B2 and C1 levels, indicating a generally stronger English background upon admission.

Figure 4.8: English Proficiency upon Entering University: Public vs. Private Universities

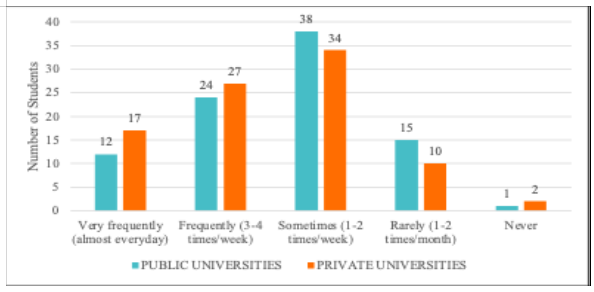

Moving to learning behaviors, the data shows that the most common frequency of practicing English outside the classroom was “Sometimes (1-2 times per week),” followed by “Frequently (3-4 times per week).” Private university students demonstrated a slightly higher percentage practicing English very frequently (almost every day) compared to public university students.

Figure 4.9: Frequency of Practicing English Outside the Classroom: Public vs. Private Universities

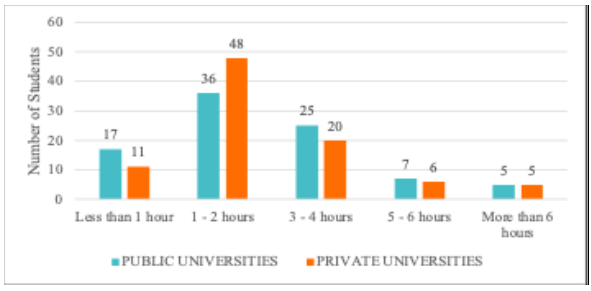

Regarding self-study time, the majority of students in both groups reported studying 1 to 2 hours per day. Private university students were more consistent within this range, while public university students showed greater variation, including a higher proportion studying less than one hour daily.

Figure 4.10: Daily Self-study Time for English: Public vs. Private Universities

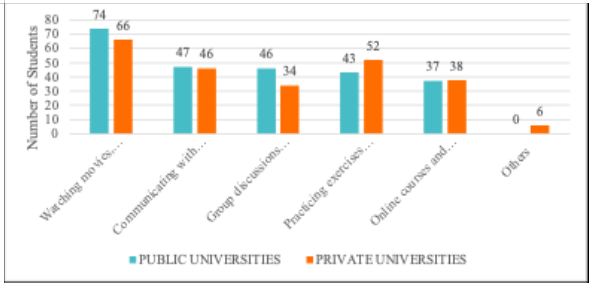

When inspecting preferred learning techniques to keep motivation, both groups desired looking English films and analyzing English books. Private college students leaned greater closer to training sports and ridicule tests, even as public university college students preferred group discussions and teamwork, indicating differing mastering choices and strategies between the two agencies.

Figure 4.11: Preferred Learning Methods to Maintain Motivation: Public vs. Private Universities

Institutional support and learning environment

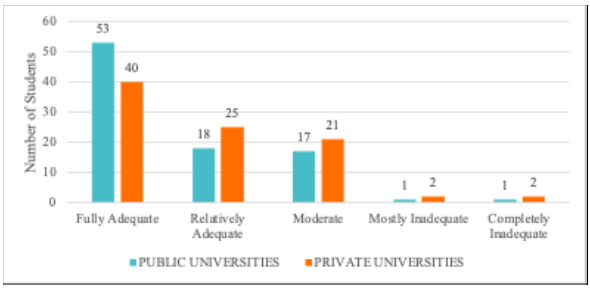

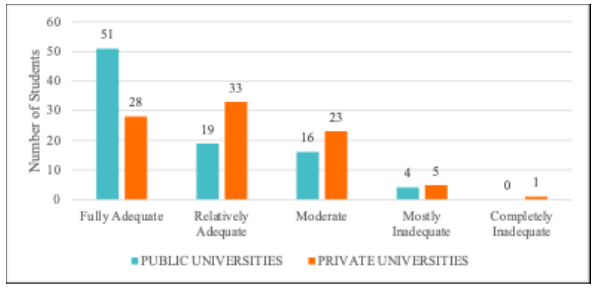

Students’ perceptions of institutional support and the learning environment for English learning revealed notable contrasts between the two groups. In terms of university support, public university students generally expressed higher satisfaction levels, with the majority perceiving their university’s support as “Fully Adequate.” Private university students, however, showed a more diverse response, with a higher proportion expressing dissatisfaction.

Figure 4.12: Students' Perception of University Support for English Learning: Public vs. Private Universities

Regarding the English learning environment, public university students again rated their environment more positively, with the largest portion selecting “Fully Adequate.” Private university students’ responses were more evenly distributed, with a considerable number perceiving the environment as only “Moderate” or “Inadequate.”

Figure 4.13: Students' Perception of English Learning Environment at University: Public vs. Private Universities

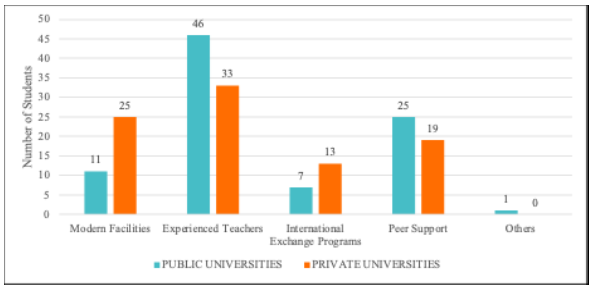

When asked about the greatest benefit of learning English at their universities, students from both groups cited experienced teachers as the most significant benefit. However, public university students valued peer support more highly, while private university students placed greater emphasis on modern facilities.

Figure 4.14: The Greatest Benefit of Learning English at University: Public vs. Private Universities

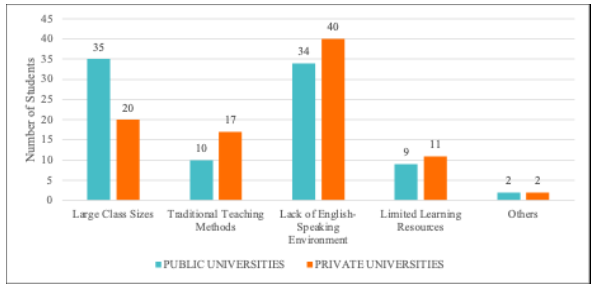

Regarding the greatest challenge, public university students identified large class sizes and the lack of an English-speaking environment as key obstacles. Meanwhile, private college students also highlighted the shortage of English-speaking surroundings as their pinnacle challenge, along with conventional teaching methods and restrained scholar engagement.

Figure 4.15: The Greatest Challenge in Learning English at University: Public vs. Private Universities

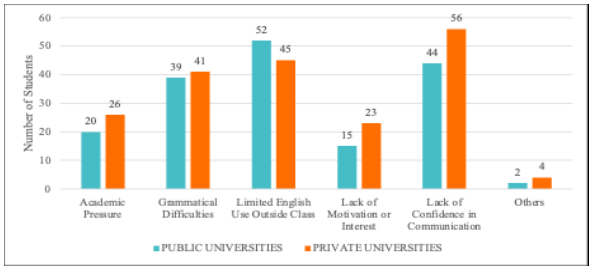

In phrases of specific problems in gaining knowledge of English, both corporations stated restrained opportunities to use English outdoor the school room and a lack of confidence in communication as primary obstacles. Notably, personal college students positioned slightly more emphasis on mental demanding situations, including peer strain and self-belief problems, even as public college students focused more on environmental and infrastructural boundaries.

Figure 4.16: Difficulties Encountered When Learning English: Public vs. Private Universities

Discussion

The findings suggest that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence students’ English learning motivation. Career-associated desires and private interest in English emerged because the maximum powerful motivators across each groups. However, public university college students regarded to be more stimulated by using commencement requirements and institutional pressures, while non-public university college students confirmed more potent intrinsic motivations, consisting of non-public development and international possibilities. This displays the interplay among non-public ambitions and institutional demands in shaping mastering motivation.

Students’ learning behaviors demonstrated differences in frequency, self-study time, and learning preferences. Private university students generally engaged in more consistent and frequent self-study and practiced English outside the classroom more regularly. They also favored structured learning methods such as exercises and mock tests. In assessment, public college students desired institution discussions and exhibited a wider range of self-look at periods. These styles advocate that private university college students have a tendency to adopt more disciplined, examination-oriented getting to know strategies, even as public university students depend extra on collaborative tactics.

Perceptions of institutional support and the learning environment also varied notably. Public university students expressed higher satisfaction levels regarding both institutional support and the learning environment, despite reporting infrastructural limitations and large class sizes as key challenges. Conversely, private university students perceived more gaps in the learning environment, especially the lack of an English-speaking atmosphere and engagement in class activities. This highlights the need for both groups to enhance practical English use and foster supportive learning spaces.

Overall, the study identified several key differences between the two groups. Private university students exhibited more diverse motivations and a stronger tendency toward autonomous and goal-oriented learning behaviors. They also perceived more psychological barriers and challenges in engagement. Meanwhile, public university students demonstrated more uniform motivations tied to institutional requirements and relied more on peer collaboration but struggled with infrastructural challenges and large class sizes. These differences underline the influence of institutional characteristics on students’ motivation, learning behaviors, and perceptions of support.

Conclusion

This paper explored the mastering motivation of senior English majors from decided on public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City. The research findings indicated that each intrinsic and extrinsic motivation plays essential roles, with career desires and personal hobby rising as the most enormous drivers. However, notable distinctions were found between students of the two university sorts.

Students from private universities displayed stronger intrinsic motivation and more autonomous, structured learning behaviors, focusing on exercises and mock tests. Conversely, students from public universities exhibited more uniform motivations driven by institutional demands, showing greater reliance on peer support and group discussions.

Despite private university students demonstrating higher self-reported English proficiency upon university entry, they also faced more psychological barriers, such as lack of confidence and pressure from peer comparisons. Public university students, while generally more satisfied with institutional support and the learning environment, struggled with infrastructural limitations, large class sizes, and lack of English-speaking environments.

These findings confirm that institutional contexts significantly shape motivational factors, learning behaviors, and perceived challenges in English learning among students from different types of universities.

References

Anjomshoa, L., & Sadighi, F. (2015). The importance of motivation in second language acquisition. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature, 3(2), 126-137. https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v3-i2/12.pdf

Bontempi, E. (2023, August 14). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: implications in school, work, and psychological well-being. Excelsior College. https://www.excelsior.edu

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3), 363–423.

Chau, Q. (2022). Vietnam's private higher education. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361449108_Vietnam%27s_Private_Higher_Education

Chau, Q., Dang, B. L., & Nguyen, X. A. (2020). Patterns of ownership and management in Vietnam’s private higher education: An exploratory study. Higher Education Policy, 33(3), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00143-4

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.2307/330107

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Innovations and challenges in language learning motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 593824. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.593824

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Gardner, Tremblay, and Masgoret (1997). Towards a full model of second language learning: an empirical investigation. The Modern Language Journal, 344-362.

Inngam, P., & Eamoraphan, S. (2014). A comparison of students’ motivation for learning English as a foreign language in selected public and private schools in Bangkok. Scholar: Human Sciences, 6(1). http://www.assumptionjournal.au.edu/index.php/Scholar/article/view/48

Luo, M. N., Stiffler, D., & Will, J. (2017). The long-term outcomes of graduates’ satisfaction: Do public and private college education make a difference? Journal of Global Education and Research, 1(1), 11–24. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu

Ma, F. (2015). A review of research methods in EFL education. Theory and Practice inLanguage Studies, 5(3), 566–572. http://academypublication.com/issues2/tpls/vol05/03/16.pdf

Masgoret, A. M., & Gardner, R. C. (2003). Attitudes motivation, and second language learning: A meta-analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates, Language Learning. 21-167

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). Harper & Row.

Mazumder, Q. H. (2014). Student motivation and learning strategies of students from USA, China and Bangladesh. International Journal of Learning and Development, 4(2), 67-85. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1091729.pdf

Mazumder, Q. H., & Ahmed, K. (2014). A comparative study of motivation and learning strategies between public and private university students of Bangladesh. Proceedings of the 2014 ASEE North Central Section Conference. https://asee-ncs.org/proceedings/2014/Paper%20files/aseencs2014_submission_61.pdf

Teravainen-Goff, A. (2022). Why motivated learners might not engage in language learning: An exploratory interview study of language learners and teachers. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221135399

Vincent, T. V., & Kumar, M. S. (2018). Motivation: Meaning, definition, nature of motivation. The Yogic Journal, 4(1), 492–497. https://www.theyogicjournal.com

Yılmaz, O., & Sahan, G. (2023). A study on the motivation levels and problems in the language learning for the higher education learners. World Journal of Education, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v13n1p1

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

A survey on Learning Motivation of Senior English Majors Between Some Public and Private Universities in Ho Chi Minh City

Trần Bảo Huân, VietnamRegulating Learners՚ Engagement: A Journey of Self-discovery

Anestin Lum Chi, Cameroon